Earth Science Week Classroom Activities

The Great Ocean Conveyor

Activity Source:

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Adapted with permission.

In January 1992, a container ship headed to Tacoma,Washington, from Hong Kong, China, lost 12 containers during severe storm conditions. One container held a shipment of 29,000 bathtub toys. Ten months later, the first of these plastic toys began to wash up onto the coast of Alaska. Driven by the wind and ocean currents, these toys continued to wash ashore during the next several years, and some even drifted into the Atlantic Ocean.

The ultimate reason for the world’s surface ocean currents is the sun. Solar heating creates wind that blows over the ocean, generating surface waves by transferring some of the wind’s energy in the form of momentum, from the air to the water. This constant push on the surface of the ocean is the force that forms surface currents.

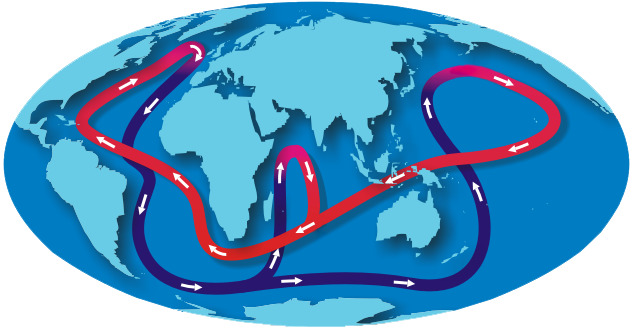

While these currents represent shallow-level circulation, global circulation extending to the depths of the sea is known as the “Great Ocean Conveyor.” Also called the thermohaline circulation, the Great Ocean Conveyor is driven by differences in density of sea water, which in turn is controlled by temperature (thermal) and salinity (haline) factors. Each winter, as new sea ice forms in the far North Atlantic Ocean, the salt left behind in the ocean makes the water very dense. This dense water sinks to the ocean floor and is the “engine” for Great Ocean Conveyor’s motion.

NOAA

This deep, slow, southward-flowing current follows a route through the Atlantic Basin around South Africa and into the Indian Ocean and on past Australia into the Pacific Ocean Basin. Scientists estimate that the deep, salty water sinking to the bottom of the North Atlantic Ocean takes between 1,000 and 1,200 years to rise to the upper levels of the ocean.

Materials

- Approximately 1-gallon clear container (such as fish bowl, bowl, or pitcher)

- Ice cube tray

- Two food colorings (for example, red and blue

- Table salt (about three tablespoons)

- Water

Procedure

-

Day 1: Mix the darker food coloring into water and fill half of the ice cube tray. Mix salt and the lighter food coloring into water and fill the other half of the ice cube tray. Freeze the solutions.

-

Day 2: Fill the clear container nearly full with room-temperature water. Allow the water a minute or two to settle.

-

Gently add one cube of each color into the water.

-

Describe what you see happening. Are the colors moving? Which direction are they moving? How fast are they moving? What do you know about water, water temperature, and salty water that may explain your observations?

-

Add more cubes if necessary to see the movement of colors in the water. In both cases, the colors sink to the bottom of the bowl. The cool water from the melting ice cubes sinks because it is denser than the surrounding water. Is the water from the lighter-colored cube sinking faster than the water from the darker-colored cube? Why would that happen?

To learn more about oceans, climate, weather, and atmosphere visit the Jetstream Online School for Weather.